Regular readers know I spent an amazing week in Baja Mexico during July, where gauzy beachwear was the norm. Now, imagine your favorite version of such a lightweight summer top and you have the perfect reminder of how to hold your next presentation: lightly. Contrast that to the tightness of a form-fitting black turtleneck, which constricts and clutches at your torso, stretching a bit in unflattering ways over a few pounds you may have picked up during COVID-19. (And when I say you, I mean me.)

As you approach a presentation, story, or talk, it’s crucial you prepare but—in my mind—equally crucial that you not commit the talk to word-for-word memorization. The risk of sounding robotic runs higher for those who memorize fully. Further, if you forget the precise word you meant to use, you can easily look frozen, like a deer in headlights, adding pressure to an already stressful situation.

For those concerned that they may come off as unprepared without memorizing, I suggest this: memorize just the opening and closing as well as the outline. Know precisely how you wish to begin and where you want—as my friend Raymond Nasr says—the plane to land. Commit to memory the 3 to 5 (at most) points that will move you from opening to closing. Then, familiarize yourself with the content, but don’t try to memorize it. Allow it, like a gauzy blouse, to blow a bit in the wind. This will enable you to be conversational, not canned, and give you the freedom to spend time where you need for a particular audience’s interests or requirements.

Allow me to drill down on these ideas a bit with six specific actions to allow you to do this.

Move from manuscript to outline and eventually just to key terms. Some talks require that you write (or type) them out completely. Leaders speaking in a language other than their primary tongue may want to have a full text before they start rehearsing. But work towards the goal of getting to outline soon and eventually just to key terms. This tactic is first for a reason—it’s the most crucial step in being a conversational speaker.

Envision a huge time shift and rehearse accordingly. Most often, this means your speaking time has been cut in half or even less. Don’t just speak faster; know what is essential to say and what cannot be cut. And, for fun, imagine what story you can add or what research you can mention if given an extra fifteen minutes. As an educator, I nearly always have an activity I can deploy to seal in my point.

Create a pocket quote to aid with both memory and conviction. I claim I learned this from my husband, the minister, but maybe I taught it to him. The trick is to put a single compelling quote related to your topic on an index card that will fit easily into your pocket. Create a second note card that contains your outline and main message. If at any point you feel lost, simply say “One quote I appreciate on this topic is from ‘insert name here’” and pull out the card and read the quote. Simultaneously, you can look at the outline before returning both cards to your pocket.

Record the full talk and listen at your leisure. Particularly in cases where you have a specific time limit, it may be crucial to know your presentation fits within it. I suggest making a simple audio recording with your smartphone. You can then play it back while you wash dishes, exercise, or fold clothes. The goal here is not, as you know by now, word-for-word memorization, but simply “muscle memory” and familiarity. By hearing it in your own voice in a variety of settings different from where it will occur, you allow it to seep into your system. Some of my clients have even told me they fall asleep to the recording, which helps them “own it” on a subconscious level.

Alter the order and see what you learn. Perhaps you can tell the story first, or move the history of the firm to the end. Founders often vary when and how they discuss their team. You reinforce the flexibility of the flow if you can rehearse the talk with different orders. I teach Russell/Munter’s AIM framework often but have fun sharing it as the MIA or IAM framework to emphasize different elements.

Rehearse from the middle out, at least a few times. Often speakers practice a presentation always starting from the opening. If they get interrupted or distracted, restart from the beginning. My friend Burt Alper suggests this habit makes the opening very strong but may consequentially weaken the ending. See what happens if you start a few times from the middle to the end or even just deliver your final 60 seconds to help end on a high note.

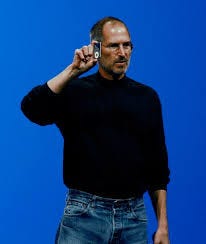

Certainly, some speakers have done well wearing black turtlenecks,

and perhaps some have even successfully held their talks in the same way, but for the rest of us, I suggest trying the strategies above.

As always, I LOVE hearing from readers to know what works and what else you suggest.

JD’s Recommendations: what I’m reading, hearing, and seeing:

Reading: Who knew Adam Grant had a newsletter, Granted, right here on Substack? Check it out.

Hearing: I’ve just become a regular listener to Morra Aarons-Mele’s The Anxious Achiever and cannot recommend it highly enough. It rocks!

Seeing: Ken and I were moved to tears as we watched Pride on Disney+. The Pixar SparkShort Out really captures the pain and energy it takes to be closeted. (Love the dad in this short!)

As always, jds

PS: If you are one of my nearly 1,000 subscribers … THANKS.

Can you do me a favor and invite one other person to subscribe?

It would mean the world to me to double my subscribers by the end of September.

Hi JD. These are solid tips ... I particularly liked the note card trick and also work to have a strong opening and closing to my talks. I think it was Tyrone Guthrie who said that "if you have a strong opening and closing to the first and second acts, people will love the play." Plus, if you blank out as you walk out on stage and look at the audience, it is good to have the first few minutes memorized and on automatic. Once you are walking it all comes back. Good stuff!

Great tips JD.